Valuing domestic work,

a springboard for gender equity strategies

By Edmée Marthe Ndoye

In 2019, the ILO’s Breakthrough Report on Gender Equality, recognizes that the greatest source of inequality between men and women worldwide is the burden of Unpaid Domestic Work (UDW) placed on women, and in particular, caregiving activities. This recognition is a major step forward in the feminist struggle for greater recognition of the domestic work performed by women, which has long remained invisible.

The domestic work in question is to be distinguished from the work of domestic servants, which is paid. By unpaid domestic work, we mean any domestic activity for which there is no monetary consideration, which is not taken into account in the national accounts and which can be carried out by a third party (Donehower, 2019), such as doing the laundry, cleaning, cooking, shopping, looking after and caring for children, the elderly, the sick, the disabled, in a family or community setting: all activities that are classified as “domestic”, which classification can be found in ICATUS 2017 (International Classification of Activities for Time-Use Statistics).

As part of the Counting Women’s Work (CWW) project, the Consortium Régional pour la Recherche en Économie Générationnelle (CREG) has appropriated the domestic work valuation tool developed under the project to assess women’s contribution to the Senegalese economy through unpaid domestic work.

How can we add value to domestic work?

On my way to work one morning, I bumped into an acquaintance and asked him about his wife. He replied: “She’s at home doing nothing”. Yet this wife didn’t have a maid. This implies that the work done by the wife all day long has little or no value in the eyes of the husband and even the community.

Indeed, valuation is the act of putting a value on something. The CWW Project and the National Time Transfer Accounts (NTTA) are working to develop this tool.

The NTTA is a tool for assessing the amount of unpaid domestic work performed by men and women at all ages. It complements the National Transfer Accounts (NTA), which failed to take effective account of gender inequalities. The NTA retrace the evolution of production and consumption of goods and services, as well as the distribution of savings at all ages in a given economy (Dramani 2019).

To value unpaid domestic work, we can consider the tariff of the activity specialist or that of the generalist. The former differs from the latter in that it pays for a service relating to a given domestic activity. The latter refers to the hourly rate of a household helper paid to carry out work on several domestic activities. The NTTA method uses specialist costing. But in the context of African countries, the valuation method favors the cost of the generalist, due to the scarcity, if not non-existence, of specialists in paid domestic activities..

What data should be used to value domestic working time?

The preferred data for valuing domestic working time are those obtained from time-use surveys. These provide detailed information on the various activities performed by the respondent during the day. The main challenge in these surveys is the treatment of simultaneous activities, which some authors agree make up at least a third of the day’s activities (Kenyon 2010).

Furthermore, time-use surveys are non-existent in most African countries. The majority of studies relating to unpaid domestic work use data from modules dedicated to time use in household surveys carried out in these countries. In Senegal, the data used to assess women’s contribution to the economy through TDNR comes from the EHCVM 2018.

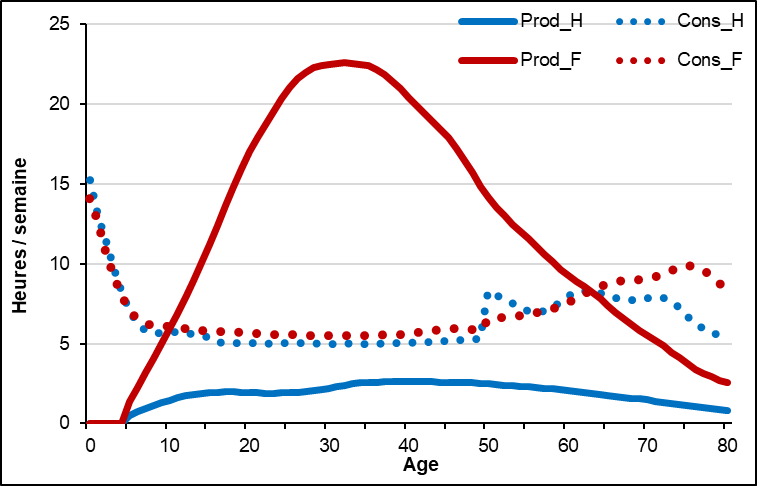

Over the life cycle, the amount of TDNR produced by women can reach over 22 hours a week, compared with around 3 hours for men.

The results obtained above are taken from the National Time Transfer Accounts (NTTA) carried out in 2018 by CREG. The National Time Transfer Accounts track production, consumption and transfer flows of unpaid domestic working time.

They reveal that in Senegal, domestic work is carried out predominantly by women over most of the life cycle. Women produce (solid red curve) more time in unpaid domestic work than they consume (dotted red curve). In other words, women devote more of their time to domestic activities than they benefit from. The opposite phenomenon is observed in the case of men, who over the entire life cycle consume more TDNR time than they produce. A 32-year-old woman spends an average of over 22 hours a week on domestic activities, while her counterpart of the same age spends less than 3 hours a week.

When we look at the consumption of domestic work time, we see that the optimal peaks are devoted to youth, between 0 and 2 years of age for all genders, and to old age from 63 onwards. This reveals the high demand for domestic care time during these periods of life.

Table 1: Production and consumption of domestic work in

Based on the principle that any TDNR time produced is inevitably consumed, we can therefore conclude that significant demand for TDNR time is covered by women’s production.

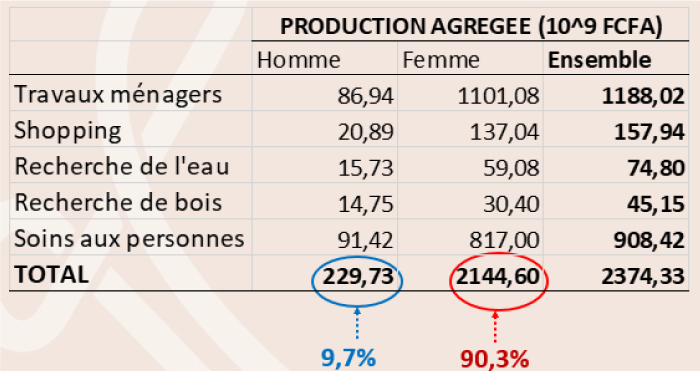

Women’s contribution estimated at 17% of 2018 GDP, compared with 2% for men

In monetary terms, the table below shows the value of women’s and men’s domestic work for each activity.

This means that women outnumber men in all domestic activities. However, the domestic activities that consume the most time and account for most of the value of domestic work are housework and personal care. Women’s contribution to the latter is respectively 13 times and 9 times greater in monetary terms than that of men.

Table 2: Valuation of domestic time: production by activity and gender in Senegal in 2018

In total, unpaid domestic work stands at 2374.333 billion FCFA for the 2018 account. This sum represents 19% of GDP, i.e. 17% for women and 2% for men.

Recommendations

These results show that women are time-poor, as they spend most of their time in TDNR. For greater gender equity in access to the labor market, public policies must take account of TDNR as a “social good” that contributes to the population’s well-being. This could be achieved through subsidies for TDNR, greater formalization of the care sector and investment in quality domestic work, in particular the personal care sector, including early childhood education establishments, crèches and care facilities for the elderly and disabled.